Windows Security Updates for Hackers

Frequently colleagues and clients get to my (virtual) desk and pose the following question to me: “I know which patches (KBs) are installed on a Windows system, but how do I know what risks it is exposed to?”. This is a very good question and I am sure there are many more people who are wondering the same when for example testing a client’s environment or while working on the OSCP training lab. The challenge is that by simply looking at the list of installed KBs there is no easy way to know what the vulnerabilities the system is exposed to.

In this blog we will look at how Windows versioning works and then go through the steps of obtaining the Windows version information and list of installed KBs from the local or a remote system. With this information we are then able to quickly identify vulnerabilities for the system they are attacking and, if available, use an exploit to extend their foothold. This will help us to quickly assess the risk the system is exposed to. The Windows Exploit Suggester - Next Generation tools wes.py and missingkbs.vbs that I developed will support the identification process as efficiently as possible.

Before diving into how to identify missing KBs, let’s first get some context on how Windows releases work.

Windows Operating Systems

From its Windows OS, Microsoft provides both a client and a server variant. These variants share the same kernel but are aimed for different purposes. The server variant is designed serve in a variety of roles like domain controller, web server and virtualization host which allows use on very powerful hardware. The client variant is designed for daily use by home, school and business users for use like text processing, web browsing and playing games. New versions of both the client and server OS are released regularly where at the moment of writing respectively Windows 11 and Windows Server 2022 are the latest releases of the OS. Previous versions are (in descending date) Windows 10 (build 1809)/Server 2019, Windows 10 (build 1607)/Server 2016, Windows 8.1/Server 2012 R2, Windows 8/Server 2012, Windows 7/Server 2008 R2, Windows Vista/Server 2008 and Windows XP/Server 2003 [R2]. The full list of Windows versions is available on Wikipedia1.

In addition to the two variants, Microsoft also distinguishes between different editions within the client and server variants. Both variants have a number of editions which depending on the variant differ in functionality2, license restrictions and update cycles and support3 4 5. In this blog the focus will primarily be on Windows 10 and its server variant Windows Server 2016 and later.

As Microsoft does not support OSs forever, there is a sliding time window of OSs and versions that are still supported and those who are end of life. Once a product reaches its end of life, Microsoft does not provide security updates to the OS anymore and therefore any future vulnerabilities discovered will not be patched anymore, although in some rare cases an exception is made. One of such exceptions is the security update for the end of life Windows XP, 8 and Windows Server 2003 to mitigate the Eternal Blue vulnerability6. Depending on the Windows edition, there are three update channels which differ with regards to the pace at which new features are added and are also directly related length of the support. Every release in the channel can be considered as a milestone at which new features are added to the OS.

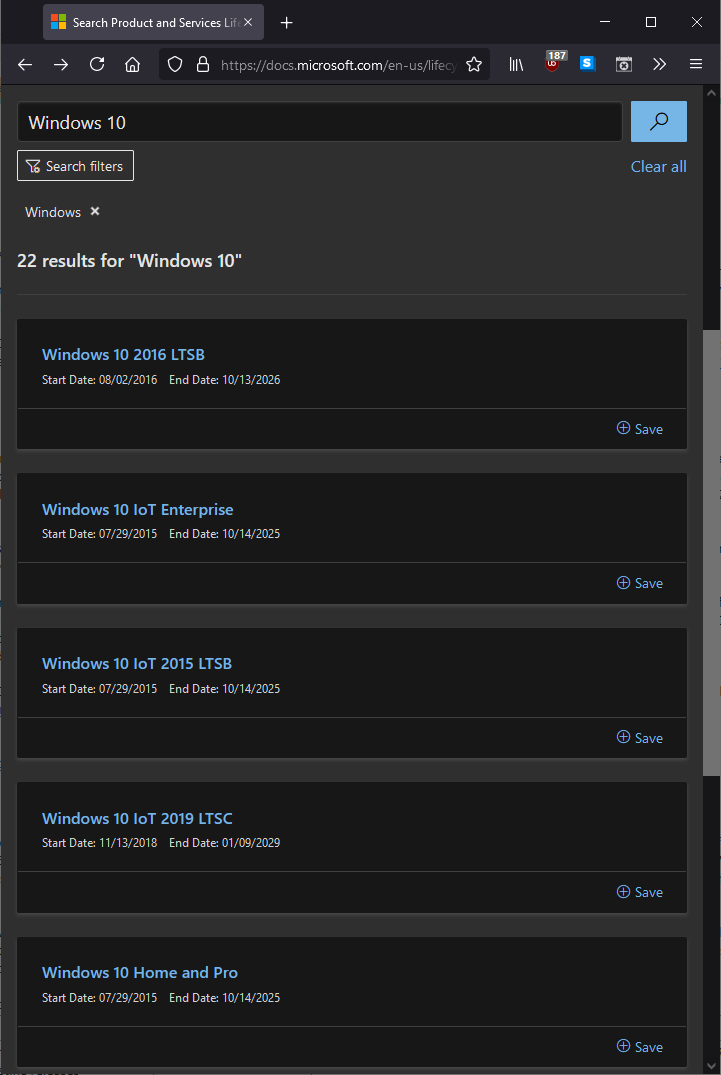

A good first check to perform is to identify whether the OS is still supported. This can be checked by searching the Lifecycle documentation website for the Windows version you have encountered. The URL for this website is: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/lifecycle/products/?products=windows.

Example with search for Windows 10: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/lifecycle/products/?products=windows&terms=Windows%2010

Example with search for Windows 10: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/lifecycle/products/?products=windows&terms=Windows%2010

Release channels

The consumer editions of Windows 10 (Home and Pro) only have 18 months of support while the business (Enterprise and Education) versions of Windows 10 have 30 months of support in case of the fall release. These Windows 10 versions are released every 6 months and are part of the so-called Semi-Annual Channel (SAC). In addition to the consumer and business versions of Windows 10 there is also a special version aimed for use in specialized environments like ATMs and medical equipment. This version provides 10 years of support and is released every 2-3 years as part of the Long-Term Service Channel (LTSC).

In case of Windows Server there are also two editions. Windows Server appended with a year (Windows Server 2016, Windows Server 2019, …) is part of the LTSC and is released every 2-3 years with 10 years of support. The other Windows Server edition is appended with the release name instead and is part of the SAC with 18 months of support5. An example of such SAC release is Windows Server, build 2004. SAC releases don’t include the Desktop Experience feature (graphical UI for Windows Server)7.

The following table lists the support duration of the various channels.

| Channel | Feature updates | Support | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insider Program | As soon as a new feature has been released; this includes beta/testing releases | 18 months | The Insider Program is again split up in three paces: Fast, Slow and Release Preview |

| Semi-Annual Channel (SAC) | Every 6 months | 18 months (+12 months) | Formerly known as Current Branch (CB). Extra 12 months of support in case of the fall release of the Enterprise and Education edition. This fall release was formerly known as Current Branch for Business (CBB) |

| Long-Term Service Channel (LTSC) | Every 2-3 years | 10 years | Formerly known as Long Term Servicing Branch (LTSB). List of LTSC releaseas available from here8 |

The releases used to be named YYMM where YY is a 2-digit year followed by MM which is a 2-digit month, for example 1909 for the September release in 2019. Starting from the Windows 10 fall release in 2020 this has changed to a YYH1/YYH2 half-year pattern9. This means that the Windows 10 release of May 2021 is called 21H1. The names of these releases are used in the output of various tools which display OS version information in Windows which we will get to in a later section.

From the moment of the release, the number of months (or years in case of LTSC) of support start counting. The periodic releases in the various channels the updates can be downloaded through Windows Update, the Microsoft Update Catalog10 and Windows Server Update Services (WSUS). Additionally, .iso disk images are released for clean deploys.

Security updates

Now it is clear how to determine whether a specific OS version is supported or end of life, it is time to look at security updates. Although in case of urgent vulnerabilities security updates might be deployed outside of the regular monthly schedule, Microsoft generally releases security updates every 2nd Tuesday of the month. This day is called Update Tuesday11, however popularly this day is also called Patch Tuesday.

In the Microsoft world every security update (and also non-security updates) can be identified using a Knowledge Base (KB) article ID. This KB number can be used at the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) Security Update Guide12 to obtain more information about the exploitability of a certain vulnerability. At the Microsoft help pages there is more information about the security update and the Microsoft Update Catalog10 provides links to download the security update installation file and get information about superseding KBs. Besides KB these security updates are also called hotfixes and patches. In this blog these names are used interchangeably.

Below a table with the various resources Microsoft provides around security updates.

| Name | Link | Information |

|---|---|---|

| MSRC Security Update Guide | https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide | List of latest CVEs and associated KBs for Microsoft products with links to details about the exploitability, the KB article and download link to the security update |

| Microsoft Help pages | https://support.microsoft.com/help/[KBID] | High level information on what the security update fixes, which potential issues it may cause and instructions on how to obtain the update |

| Microsoft Update Catalog | https://www.catalog.update.microsoft.com/Search.aspx?q=KB[KBID] | Provides downloads for the security updates for the various Windows versions and at the Package Details tab information about which previous updates are superseded by this update or supersede this update |

Determining installed security updates

As a hacker we would like to determine whether a certain system is missing security updates and if so, make note of it or even use an exploit to abuse the vulnerability and get access or escalate. Before being able to identify which security updates are missing, first the details on the OS version in combination with the currently installed patches are required.

There are a variety of ways to retrieve this information, both from the local system as well as from remote systems given that the account running the command has sufficient privileges to access the remote system. Depending on the approach the information about the OS version and the installed security patches are obtained using the same command or different commands. Additionally, GUI tools like winver.exe, msinfo32.exe and the View installed updates section in appwiz.cpl are built into Windows, however from these tools the information cannot be easily exported to a file to be processed at a later stage, so we will not focus on these tools.

systeminfo.exe

systeminfo.exe is a utility which is built-in to Windows since the earliest versions of Windows. This tool lists both the installed patches as well as the Windows version and is also able to collect this information from a remote system. To obtain the information from a remote system the /S parameter can be used. Either the identity under which the current process is running should have permissions on the remote system or the credentials need to be provided using the /U and /P parameters. This command heavily relies on Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) to collect the information on both the local and remote system.

WMIC.exe

WMIC.exe is the WMI command line utility which allows to both query WMI and invoke functions in WMI, both locally and remotely. As discussed in the systeminfo.exe utility paragraph, WMI provides classes which when queried list the details of the OS and the security updates that are installed. These classes are respectively the Win32_OperatingSystem class and Win32_QuickFixEngineering class which both reside in the root\CIMv2 namespace. The WMIC.exe utility provides aliases for these classes, namely OS and QFE, but the full class names can also be used.

PowerShell cmdlets

PowerShell provides the Get-ComputerInfo and Get-HotFix cmdlets to respectively obtain information about the local computer, and lists the installed hotfixes on both the local and remote system. The Get-ComputerInfo cmdlet was added from PowerShell version 5.1. Underlying both commands again use WMI to obtain the relevant information. The Get-ComputerInfo and Get-HotFix cmdlets can be executed on a remote system through WinRM using the Invoke-Command cmdlet, but that is outside of the scope of this blog.

WMI through PowerShell

Instead of using the WMIC.exe utility, it is also possible to use PowerShell’s built-in Get-WmiObject cmdlet (or additionally the Get-CimInstance cmdlet from PowerShell version 3). With these cmdlets again the Win32_OperatingSystem class and Win32_QuickFixEngineering classes can be queried, both locally and remotely. In case you need to stealthily connect this information during red team exercises, these cmdlets are also supported by the NoPowerShell .NET binary.

Non-native tools

In addition to the built-in Windows utilities and PowerShell cmdlets there are a few tools which are also able to obtain the OS version information and installed security updates. Two examples of such tools are srvinfo.exe which is part of the Windows Server 2003 Resource Kit13 and psinfo.exe14 which is part of the Sysinternals suite, nowadays maintained Microsoft. Finally, the missingkbs.vbs utility which is part of the Windows Exploit Suggester - Next Generation (WES-NG) tool not just lists the installed patches, but instead accurately determines the missing patches. This utility will be extensively discussed in the Microsoft Update section.

The following table summarizes all commands as described above where the binary utilities have the .exe extension whereas the others are PowerShell cmdlets.

| OS version | Security updates | Locally | Remotely | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | systeminfo.exe |

systeminfo.exe /S MYSERVER |

Optionally provide /U MyUser and /P MyPassword parameters. On Windows Server 2003 (and maybe other OS version), systeminfo.exe might not list all installed KBs if the number of installed KBs is over 200. Microsoft article on this issue available here15. |

| X | WMIC.exe OS |

WMIC.exe /node:MYSERVER OS |

||

| X | WMIC.exe QFE |

WMIC.exe /node:MYSERVER QFE |

||

| X | X | Get-ComputerInfo |

n/a | List of installed patches available in the OsHotFixes attribute. Available from PowerShell 5.1. |

| X | Get-HotFix |

Get-HotFix -ComputerName MYSERVER |

||

| X | Get-WmiObject Win32_OperatingSystem | fl * |

Get-WmiObject -ComputerName MYSERVER Win32_OperatingSystem | fl * |

||

| X | Get-WmiObject Win32_QuickFixEngineering |

Get-WmiObject -ComputerName MYSERVER Win32_QuickFixEngineering |

||

| X | / | srvinfo.exe |

srvinfo.exe \\MYSERVER |

From Windows Server 2003 Resource Kit13. On Windows 10 (and possibly earlier OSs) the list of hotfixes is not accurate. |

| X | / | psinfo.exe -h |

psinfo.exe -h \\MYSERVER |

Part of the Sysinternals suite14. The -h flag to list the installed hotfixes does not seem to work on Windows 10 (and possibly earlier OSs). |

| X | X | cscript.exe missingkbs.vbs |

n/a | List missing patches using WES-NG’s missingkbs.vbs utility. This utility will be extensively discussed in the Microsoft Update section. |

For further processing it is useful to store the information outputted by the above utilities and cmdlets in a file. This can be done by redirecting the standard output (STDOUT) of the tool to a file. When launching the (.exe) utilities from a Command Prompt (cmd.exe), this can be done by appending > myfile.txt at the end of the command. For example in case of systeminfo.exe, use the following command line.

systeminfo.exe > systeminfo.txt

In case of PowerShell the redirector symbol (>) can be used (Get-HotFix > hotfixes.txt) or the output can be piped to the Out-File cmdlet, optionally providing the type of encoding that needs to be used using the -Encoding parameter. Moreover, in case only data from a specific attribute is needed, this attribute can be specified with the ForEach-Object cmdlet (or alias %) and subsequentially piped to the Out-File cmdlet, for example:

Get-HotFix | % HotFixID | Out-File -Encoding ascii hotfixes.txt

Identifying missing security updates

Once the Windows version information and installed security updates have been collected, the next step is to identify which security updates are missing. The files created in the previous section can be copied locally for further investigation to identify vulnerabilities and potential available exploits.

As discussed in the Security updates section, the Microsoft Update Catalog10 provides information on the superseding of KBs. It would be possible to look up each and every KB and identify by which newer KBs this KB has been superseded and check if those KBs in turn as well have been installed in a recursive manner. This would however result in a lot of work going through all of the KBs and checking whether they have been superseded. This is where the Windows Exploit Suggester - Next Generation (WES-NG)16 utility I developed comes to rescue. WES-NG uses the MSRC dataset to identify the supersedence links between the various KBs and connects these through the Common Vulnerability and Exposures (CVE) IDs with potential exploits that might be available for the vulnerabilities. More about these data sources later in the Dataset section.

WES-NG is by default included in the BlackArch Linux penetration testing distribution and repository17, but can also be easily obtained on any other OS using Python’s pip utility (pip install wesng) or by simply cloning the WES-NG repository: git clone --depth 1 https://github.com/bitsadmin/wesng.

Windows Exploit Suggester - Next Generation

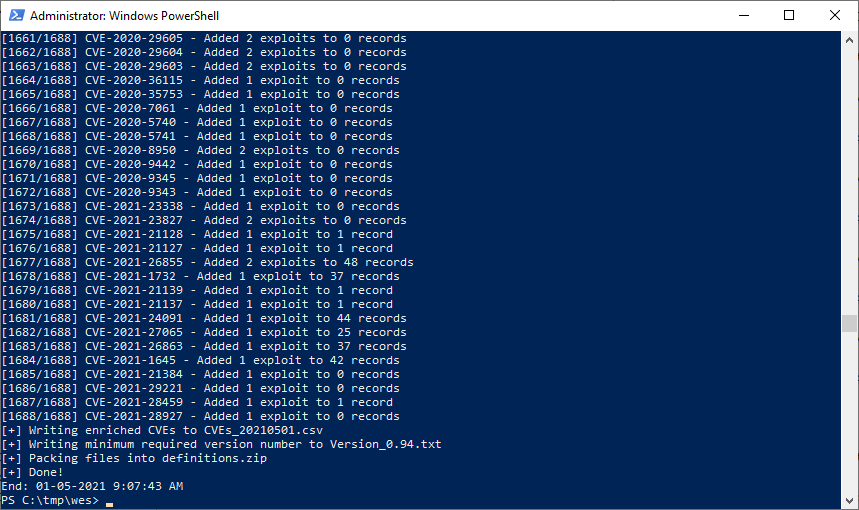

WES-NG’s wes.py script is a Python 2/3 tool which uses an exploit definitions file and checks for missing patches based on the OS version and the list of patches that are installed. WES-NG subsequently automatically iterates the chain of superseded patches. To get started with wes.py, first the latest definitions file needs to be downloaded using the --update (shorthand: -u) parameter which will download the latest definitions.zip file to the current directory. Next, wes.py can be executed with a previously extracted systeminfo.txt file and optional qfe.txt file with the list of installed KBs as a parameter. For a full list of all supported parameters including various examples, execute wes.py --help (shorthand: -h).

When executing, wes.py will first determine the OS version from systeminfo.txt and collect all KBs ever released for that OS version from the definitions.zip file. From this list all KBs that are installed on the system are removed, including the KBs which have been superseded by the installed superseding KB. This step is performed recursively so the full chain of KBs which is superseded by the installed KB is removed. After validating all the KBs applicable to the OS version only the ones that are not installed are listed as missing KBs. Finally, for every KB the CVEs are identified which would be mitigated if the KB is installed. These CVEs are then listed including the following information.

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Date | Date in yyyyMMdd format at which the KB was published |

| CVE | CVE for which the system is vulnerable |

| Affected product | OS version |

| Affected component | Software component on the system which is vulnerable |

| Severity | Severity of the CVE |

| Impact | Impact to the system when the CVE is exploited |

| Exploit | Link(s) to PoC exploit code, in case it is publicly available |

Filtering

Additionally the vulnerabilities from the output of WES-NG can also be filtered. This is for example useful if an attacker is interested in vulnerabilities that can result in remote code execution and/or only vulnerabilities that have exploit code available. Respectively the --impact "Remote Code Execution" (shorthand: -i) and --exploits-only (shorthand: -e) parameters can be used for this. Additionally also results for certain products can be hidden using the --hide parameter or only results with a certain severity can be listed using the --severity (shorthand: -s) parameter. To get the full overview of parameters including examples check the output of the --help command, which is also listed in CMDLINE.md.

WES-NG by default outputs the results to the console. For further analysis however, WES-NG also supports storing the results in CSV format to disk using the --output (shorthand: -o) parameter, e.g.:

wes.py systeminfo.txt -o srv01.csv

See below an animation from collecting the OS version and missing patches to identifying the missing patches using WES-NG, including the use of some filters described and the csv output option.

Eliminating false positives

As you go through the results of WES-NG, it unfortunately turns out that it is also reporting false positives. For example, even on fully patched systems WES-NG might still show some KBs missing. The reason for this is because the MSRC feed which WES-NG uses to compile its definitions frequently contains incomplete information regarding supersedence of KBs.

Another point to take into account is that WES-NG assumes that all features are installed. For example in case the systeminfo.exe output file of a plain Windows Server without any roles and features installed is checked, it might report on IIS vulnerabilities for which no KBs are installed on the OS. This is because apart from the OS version and installed KBs, WES-NG does not have information about which roles and features are installed. Therefore vulnerabilities reported in components that are not installed can be safely ignored.

In order to eliminate the false positive results, there are a number of ways available.

Pragmatic way

As mentioned before security updates are released on a monthly basis. When checking a system for missing patches, a pragmatic way would be to simply check the release date of the most recent KB installed on the system and then assume that after that moment no new updates have been installed. In case due to issues with the MSRC supersedence still older KBs are listed as missing, it is pretty safe to assume that those will probably be false positives as newer KBs have already been installed. wes.py’s --usekbdate (shorthand: -d) flag will perform these steps and leave out the older supposedly missing KBs from the output. Example:

wes.py systeminfo.txt -d

Manually verify

In case the output needs to be more accurate, another option is to execute WES-NG and then manually validate the list of missing KBs at the end of the output at the Microsoft Update Catalog website. This can be done by looking up the missing KB and identifying which KBs have superseded this KB and whether that KB is actually installed in the system. If so, the KB reported as missing by WES-NG can explicitly be specified as installed so WESN-NG will not list the vulnerabilities the system is exposed to when the KB is not installed. This way a supersedence which was missing from the MSRC dataset is circumvented. In WES-NG the KB can be provided to wes.py using the -p parameter, for example wes.py systeminfo.txt -p KB4487029. Repeat this process for every supposedly missing KB where the -p parameter allows for specifying multiple KBs by separating them using a space, e.g. -p KB4487029 KB4345421. For a more detailed description of manually verifying WES-NG’s output, see the Eliminating false positives page in WES-NG’s wiki.

Automatically verify

Because manually verifying is still a tedious process, @DominicBreuker contributed a useful feature to automate the process of looking up the supersedence in the Microsoft Update Catalog by parsing the website and automatically walking the chains. This feature can be used by providing the --muc-lookup parameter to the wes.py script. After determining the missing patches based on the MSRC dataset, it will take the resulting missing patches and automatically validate each of them at the Microsoft Update Catalog.

In addition to manually and automatically validating the supersedence using the Microsoft Update Catalog, there also exists a completely different approach to identifying missing patches, which is described in the next section.

Microsoft Update

A whole different approach to identify missing KBs is to use Microsoft Update. Instead of obtaining the OS version and the currently installed version through systeminfo.exe or other ways described in the Determining installed security updates section, it is possible to use Windows’ own functionality to identify which KB are still missing from the system at the current moment in time.

missingkbs.vbs

The Windows Update control panel applet or Windows Update modern control panel page is able to list the missing KBs, but it might be tedious to retype the results and it requires a GUI which might not be available. For that reason, a script has been added to WES-NG’s repository to allow obtaining the required information from the command line: missingkbs.vbs.

The resulting file listing the missing KBs can be provided to wes.py using the --missing (shorthand: -m) parameter to exactly identify the CVEs the system is vulnerable to, circumventing all of the issues with the incomplete supersedence information provided by MSRC. Additionally, in contrast to using the list of installed patches from systeminfo.exe, the missingkbs.vbs utility also only lists missing KBs of features that are installed.

To identify missing KBs, the missingkbs.vbs utility makes use of the Microsoft.Update.Session COM object which is implemented in the wuapi.dll library. In order to be able to use the functionality of this COM object, an elevated command prompt is required when executing the missingkbs.vbs utility. For a full list of all supported parameters including various examples, execute cscript missingkbs.vbs /Help (shorthand: /?).

When executing missingkbs.vbs without parameters it will use the online Windows Update servers or if configured the WSUS server which are often used in corporate environments. Because the WSUS server is able to hold back updates for its clients there is the possibility that the WSUS server reports the system is not missing any patches while there in fact are missing ones. Moreover, in case a system is not (directly) connected to the Internet, it would still be useful to be able to check for any missing KBs.

For that reason the missingkbs.vbs utility has an option to use a Windows Update offline scan file to be able to determine the missing KBs based on this file as opposed to using the Microsoft Update/WSUS servers. This scanfile of about 1 GB can be downloaded on an Internet-connected system from the following URL: http://download.windowsupdate.com/microsoftupdate/v6/wsusscan/wsusscn2.cab.

Alternatively, this file can also be downloaded using the missingkbs.vbs utility by using the /D parameter. Next, the wsusscn2.cab file can be copied to the system which does not have Internet access together with the missingkbs.vbs utility. From an elevated command prompt the missingkbs.vbs utility can be launched with cscript.exe providing the /Offline (shorthand: /F) parameter to have it use the scanfile downloaded earlier: cscript missingkbs.vbs /F. If needed the full path to the scanfile can be provided using the /I parameter, e.g.:

cscript missingkbs.vbs /F /I:E:\tmp\wsusscn2.cab

The COM object mentioned earlier will be initialized and instructed to use the scanfile to identify any missing KBs on the local system. After execution the list of missing KBs will be printed in the console as well as stored in the missing.txt file in the current directory.

C:\>cscript missingkbs.vbs

Microsoft (R) Windows Script Host Version 5.812

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Windows Exploit Suggester: Missing KBs Identifier v1.0

https://github.com/bitsadmin/wesng/

[I] Windows Update online is used

[+] Identifying missing KBs...

[+] List of missing KBs

- KB4049411: Update for Windows 10 Version 1607 for x64-based Systems (KB4049411)

- KB4033631: Update for Windows 10 Version 1607 for x64-based Systems (KB4033631)

- KB4103720: 2018-05 Cumulative Update for Windows 10 Version 1607 for x64-based Systems (KB4103720)

- KB4485447: 2019-02 Servicing Stack Update for Windows 10 Version 1607 for x64-based Systems (KB4485447)

- KB4023057: 2020-06 Update for Windows 10 Version 1607 for x64-based Systems (KB4023057)

- KB4480730: 2020-06 Update for Windows 10 Version 1607 for x64-based Systems (KB4480730)

- KB890830: Windows Malicious Software Removal Tool x64 - v5.90 (KB890830)

- KB2267602: Security Intelligence Update for Microsoft Defender Antivirus - KB2267602 (Version 1.341.548.0)

[+] Saved list of missing updates in "C:\missing.txt"

[+] Done!

C:\>

wes.py -m

Based on the list of missing KBs it is still challenging to determine the security vulnerabilities the system is exposed to. Thats why the missing.txt result file can now be fed to wes.py to get this insight. From version 1.00 the --missing (shorthand: -m) and --os parameters have been added to wes.py to facilitate this.

Because missing.txt only contains a list of KBs that are missing from the system, it is needed to also specify the operating system. The easiest method though is to first execute wes.py with only the -m parameter: wes.py -m missing.txt. Subsequently from the list of possible operating systems in the output the ID of the relevant operating system can be picked and wes.py can be executed again, now also providing the operating system ID: wes.py -m missing.txt --os 2.

In some cases WES-NG does not have information about a missing KB. In that case the Microsoft Help pages as listed in the table in the Security updates section can be used to obtain information on the KB.

This concludes the practical part of identifying the vulnerabilities. We looked at both obtaining the list of installed KBs from the systeminfo.exe output and the more reliable missingkbs.vbs utility to obtain the missing KBs. In both cases we observed that both outputs can be provided to WES-NG which then lists the CVEs, if available including exploits, the system is vulnerable to.

The next section is a bit deeper dive in the data sources WES-NG uses to collect all of this information.

Dataset

The wes.py script makes use of the definitions.zip file which is hosted at the wesng project page in on GitHub. These definitions are updated approximately once a week to include the latest KBs, CVEs and exploit links. Therefore it is also recommended to regularly update the local copy of the definitions by running wes.py -u as described in the Identifying missing security updates section. The information stored in the definition file is collected and subsequently merged by the three collect_*.ps1 PowerShell scripts in the collector folder of the wesng repository. In this section the three data sources will be discussed.

Security Bulletins

Microsoft has been publishing so-called security bulletins18 in the form of bulletins on the Microsoft website and the BulletinSearch.xlsx Excel file in the Microsoft Download Center19. These have been published until the beginning of 2017 when Microsoft moved on to use the Security Update Guide12 of the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) to publish information about vulnerabilities. This change has been announced on the MSRC blog at the end of 201620. Those who have done their OSCP training or other work related to evaluating the patch level of Windows OSs before 2017, probably remember Windows Exploit Suggester21 by Sam Bertram from GDSSecurity (nowadays Aon’s Cyber Labs) which makes use of the BulletinSearch.xlsx file. Because older vulnerabilities were not included in MSRC’s Security Update Guide, WES-NG’s collector includes the collect_bulletin.ps1 script to collect this information and store it the bulletin.csv output file.

MSRC

The MSRC’s Security Update Guide is the successor of the security bulletins and provides both a web front-end12 as well as an API22 to provide information on vulnerabilities. WES-NG’s collector uses this API in its collect_msrc.ps1 collector script where relevant attributes are collected and stored in the MSRC.csv output file. These attributes include the KB ID, CVE ID, affected product, risk information and superseded KB IDs.

NVD

The National Vulnerability Database (NVD)23 which is provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) hosts a list of Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) records. These records provide a unique ID including some details with regards to publicly known security vulnerabilities. Details include the vendor, name and versions the CVE applies to, the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) score which details how easy the vulnerability is to exploit and what the impact of exploitation is. Lasty it provides references with further details about the vulnerability and any available exploit Proof of Concept (PoC) code.

As the CVE standard is widely adopted by software and security vendors, Microsoft also adds references to the CVE IDs that are resolved by the KB (and previously security bulletins). WES-NG’s collect_nvd.ps1 collector script therefore uses these CVEs as a link between the information from the NVD dataset and Microsoft’s datasets and enriches the KB information with links to PoC exploit code if available.

Custom

As mentioned before, unfortunately the MSRC dataset frequently contains incomplete supersedence information. For that reason it is possible to manually complement it by adding lines to the Custom.csv file. For example, custom supersedence information has been added for the MS17-010 (Eternal Blue) KB24 because MSRC is incomplete and often people want to validate whether a certain system is at risk. Moreover, additional exploit links and vulnerabilities could be added there. A better option however is to submit an update request to MITRE25 so the dataset used by many companies and individuals is enriched as opposed to just the WES-NG tool’s dataset.

At the end of the collector process, the enriched dataset is stored in the definitions.zip file, together with a text file defining the minimum required version of the wes.py script and the Custom.csv file. This definitions file is then uploaded to the WES-NG GitHub where it will be obtained when updating WES-NG using the -u flag.

Conclusion

This blog started with an explanation of the Windows Operating System (OS) lifetimes. Next, the various ways to collect information on the Windows OS and installed or missing KBs on a local or remote system have been discussed. This information was subsequentially used to determine what security vulnerabilities the system is exposed to and any public exploits that might already exist for these vulnerabilities. Tooling (WES-NG’s wes.py and missingkbs.vbs) have been introduced to make this process more efficient. Finally, the inner workings and limitations of the WES-NG tooling have been explained.

This blog and referenced tooling is focused on identifying missing patches, and with that vulnerabilities, in the Windows OS. This exercise can however be expanded by additional evaluations of supplementary software installed and running on the system. Such software could be Microsoft server software like Microsoft Exchange Server, client software like Microsoft Office but also 3rd party software like Adobe Reader. Complementing the Windows OS vulnerability information with information on software running on the system will provide an accurate perspective on the state of security of a system.

References

-

Microsoft Docs - Comparison of Standard and Datacenter editions of Windows Server 2022 ↩

-

Microsoft Docs - Windows Server 2019 - Desktop experience feature ↩

-

Windows Server 2003 Resource Kit download from archive.org ↩ ↩2

-

Microsoft Docs - SystemInfo.exe does not display all updates in Windows Server 2003 ↩

-

GitHub - Windows Exploit Suggester-Next Generation (WES-NG) ↩

-

Microsoft Download Center - Microsoft Security Bulletin Data ↩

-

Microsoft Knowledge Base - How to verify that MS17-010 is installed ↩

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 1/3: Setup Linux VM for SOCKS routing

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 2/3: Configuring the Offensive Windows VM

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 3/3: Using Windows as Offensive Platform

- Digging for Secrets on Corporate Shares

- Dealing with large BloodHound datasets