Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 1/3: Setup Linux VM for SOCKS routing

Introduction

As environments are increasingly getting more secure and monitored, attackers need to invent new ways to hack into systems whereas administrators and defenders need to prevent and detect such hacking attempts. In the past decade there has been a lot of development on both sides. Where attackers initially were simply able to run basically any payload on a system as long as they did not touch the disk, nowadays defenders have a lot more visibility thanks to next-generation Antivirus and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) software which is gradually rolling out to more and more systems in an increasing number of organizations.

In case EDR software is running and actively monitored by a SOC, attackers have some ways to proceed:

- Stay low under the radar, carefully considering the possible telemetry and alerts generated for every activity performed (which is good to do anyways);

- Attempt to disable or blind the AV/EDR software by killing its processes or unhooking functions that feed information to these security systems;

- Attempt to stay out of sight of the EDR software by going deeper and (ab)using drivers.

There is however another way forward which thus far has not been very extensively used and researched yet. This approach is to avoid performing activities on the endpoint where the EDR software is running, and instead use the endpoint as a network-level pivoting point into the target network making use of SOCKS proxy.

SOCKS is already used regularly by attackers to execute scripts over network tunnels to perform actions against systems in the target environment. In this area however there is much more to gain when one is aware of the activities Windows system administrators are able to perform from their administrative workstations on systems throughout the environment. When performing a red team engagement, the red team operator is effectively an offensive administrator in someone else’s network; why would such offensive administrator not make use of all the powerful tools and protocols that Windows has embedded into it for the reconnaissance, lateral movement and privilege escalation activities!? This however requires an advanced setup to support the routing of protocols like Kerberos to the target environment, and also specific skills to use tooling used by administrators.

This article aids seasoned red teamers in more effectively using SOCKS and the offensive functionalities of tools natively available in Windows in their operations. Additionally, less experienced red teamers are provided with an end-to-end guide of setting up their attacker machine in which the tooling performs transparent Kerberos authentication to the target environment, blending in with the legitimate activities.

The article will first discuss the setup of VMs on the attacker’s system which consists of both a Linux and a Windows VM to empower the Offensive Windows VM to access the target network. The next part will discuss how to obtain credential material from the victim system in the target network and then place it on the Offensive Windows VM. Once all prerequisites are in place, various examples are provided on how the Offensive Windows VM can be used. This will illustrate the great variety of activities that can be performed from Windows on both the target domain and systems and services in the target domain in order to accomplish the objectives set for the red team engagement. All of this is possible while largely remaining unnoticed by the EDR software on the victim system.

For performing the offensive activities on remote systems, I launched a new initiative called the Living Off the Foreign Land (LOFL) project. This project acts as a knowledgebase for attackers, administrators and defenders on what functionalities Windows provides to remotely manage other Windows systems, services and Active Directory. Living Off the Foreign Land (LOFL), as opposed to Living Off the Land (LOL), means that the LOFL Cmdlets and Binaries (LOFLCABs) are capable of performing activities from the local (Offensive Windows) system to a REMOTE system. Each of the LOFLCABs documents the type of activity that it can perform, example command-lines, potential offensive use cases and any IOCs that might be generated.

LOFLCABs are categorized as follows:

- PowerShell cmdlets (LOFLCmdlet);

- Binaries, both console and GUI (LOFLBin);

- Microsoft Management Console (MMC) snap-ins;

- VBS and CMD scripts;

- WMI classes.

Besides this project being used by attackers to use LOFLCABs to perform their activities and defenders to create alerting rules for IOCs, Windows system administrators can also greatly benefit from this project. This project can aid in efficiently managing the network, using one-liners to directly use MMC snap-ins against a remote host or using cmdlets and WMI classes in scripts to quickly collect information on a large scale or perform actions on multiple systems at once.

Finally, this article and associated LOFL-Project website can also be relevant for security incident responders to safely collect information and perform activities against a compromised domain with infected servers and workstations.

The LOFL-Project website1, inspired by the great LOLBAS2 and GTFOBins3 websites, can be found at https://lofl-project.github.io/. Besides the web interface, APIs are available to programmatically access the LOFLCABs for any automated processing. Moreover, scripts used for the setup are available in the LOFL GitHub repository4 at https://github.com/bitsadmin/lofl.

Because so far I have been the only contributor and there are many LOFLCABs, the web interface also provides a checkbox which displays the entries of which I expect they can be used as LOFLCABs, however are not yet fully documented. Any pull requests for complementing these is very much welcome at the LOFL-Project GitHub repository at https://github.com/LOFL-Project/LOFLCAB.

Because of its length, this article is split into three parts:

- Setup of Linux VM for SOCKS routing (this article)

- Configure Windows VM for Kerberos and obtaining/using credentials: Part 2

- Living Off the Foreign Land: Part 3

Before diving into the setup, it is problaby relevant to read up on the attacks that are possible from the attacker’s Offensive Windows VM using Kerberos in Part 3 of the article.

Now, let’s dive into the first part, setting up a Linux VM for SOCKs routing!

SOCKS

As Living Off the Foreign Land heavily depends on SOCKS, this article will start with an explanation on what SOCKS is and what the difference is between its various versions.

SOCKS

SOCKS stands for Socket Secure and is a protocol used for OSI model layer 4 (TCP/UDP) network communication between a client and a server through an intermediary proxy server. SOCKS is used for purposes like hiding your actual IP for privacy reasons and for reaching hosts that are not reachable directly. This looks as follows.

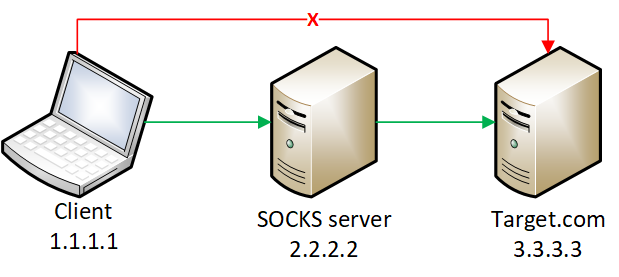

When an application is not configured to use SOCKS, it will simply connect directly to the target host. In case that is not possible, the connection will fail. However, in case like in the picture there is a SOCKS server which is able to reach the target host, this SOCKS server can send packets coming from the Client to the Target, and send responses from the Target back to the Client.

In this example we assume the application is SOCKS-aware which means it can be configured to use a SOCKS server (2.2.2.2:1080) for any network connections. On a technical level, when the application is instructed to connect, the application running on the Client (1.1.1.1) establishes a TCP connection with the SOCKS server (2.2.2.2), which by default listens on port 1080/TCP. Once the connection is established, the client requests the SOCKS server to connect to the Target (3.3.3.3), for example on port 80/TCP. The SOCKS server then attempts to establish the TCP connection to the Target (3.3.3.3:80). Assuming the connection is successful, the Client can then send data over the SOCKS server encapsulated in SOCKS, and any responses are sent from the Target to the SOCKS server which in turn sends them back to the Client. This effectively describes the functionality of SOCKS4.

SOCKS4A

SOCKS4A is a minor extension to SOCKS4 where instead of only being able to communicate with IP addresses over SOCKS, it adds the possibility to communicate to communicate with hostnames as well.

In case SOCKS4A is used, the Client application can request the SOCKS server to establish a connection with Target.com:80 (as opposed to 3.3.3.3:80 in the previous example). The SOCKS server will then resolve the domain name and establish a connection to it (in this case 3.3.3.3:80). To the client application the SOCKS server reports back a dummy, private use IP address (e.g. 224.0.0.1) which can only be used in the communication with the SOCKS server. Whenever the Client over the SOCKS server attempts to connect to that dummy IP address, the SOCKS server will make sure the connection ends up with the right host that is mapped to that dummy IP address.

SOCKS5

In addition to SOCKS4A, SOCKS5 adds the support for authentication to the SOCKS server, but most importantly IPv6 and UDP support. The UDP support tunnels UDP datagrams over the SOCKS tunnel (TCP) to the other Target side and back.

Be aware though that SOCKS5 is a standard, but software that implements the standard might only implement a subset of features of the SOCKS5 standard. At the moment of writing of this article and as will be discussed in next section, only a few implementations actually support the so-called SOCKS5 UDP ASSOCATE feature defined in the standard.

As a summary, the following table lists the different SOCKS versions, its RFC standard and what features are supported.

| Protocol | URL | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SOCKS | https://www.usenix.org/conference/sec92/socks | |

| SOCKS4 | https://www.openssh.com/txt/socks4.protocol | |

| SOCKS4A | https://www.openssh.com/txt/socks4a.protocol | Minor extension to SOCKS4 which allows connecting to a hostname in addition to only use IP addresses |

| SOCKS5 | https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc1928.txt | Compared to SOCKS4A, SOCKS5 adds support for authentication to the SOCKS server, IPv6 and UDP support. Only a few implementations support for SOCKS5’s UDP ASSOCIATE feature for dynamically connecting to UDP ports. |

Non-SOCKS aware software

Besides making use of an application which has support for SOCKS built-in, it is also possible to use software like proxychains-ng5 to force software in which no SOCKS can be configured to go over the SOCKS server. This is accomplished by proxychains-ng by launching the software which hooks any functions related to network connectivity and at the moment the software attempts to interact with the network, it will make sure in the background the SOCKS tunnel is used. An example of using proxychains-ng for the netcat network utility looks as follows: proxychains ncat -v target.com 80. Proxychains will load the ncat binary hooking the network connectivity functions and forcing those over the proxy that is configured in proxychain-ng’s /etc/proxychains.conf configuration file, e.g., socks4 2.2.2.2 1080.

Now it is clear what SOCKS is and how it can be used, the next session discusses why SOCKS is so relevant for red teaming.

Red teaming and SOCKS

During red teams often a C2 software implant is used to obtain access to a system in the target network. From that implant which resides in the memory of the system, code is executed to perform reconnaissance, discovery, lateral movement activities and depending on the objective of the engagement activities like collection, exfiltration or even deployment of (fake) ransomware.

A decade ago, the code executed from the in-memory implant used to be commands through cmd.exe or PowerShell scripts. Because detection of such behavior was increasing, this then moved to .NET assemblies in a sacrificial process spawned by the implant process. Lately security software like next-generation antivirus and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) software on endpoints are becoming more prevalent and have more visibility on the activities taking place on a system and inside of running processes. To increase operational security (OPSEC), attackers have moved more to usage of Beacon Object Files (BOFs) and .NET assemblies which are executed in the process in which the implant is running.

A disadvantage of BOFs and .NET assemblies executing on the system is however that the security software are closely watching the beacon process and its behavior interacting with the various Windows APIs. The security software might also report an alert in the security console once a threshold of malicious activities has been reached. This is where SOCKS can be of help.

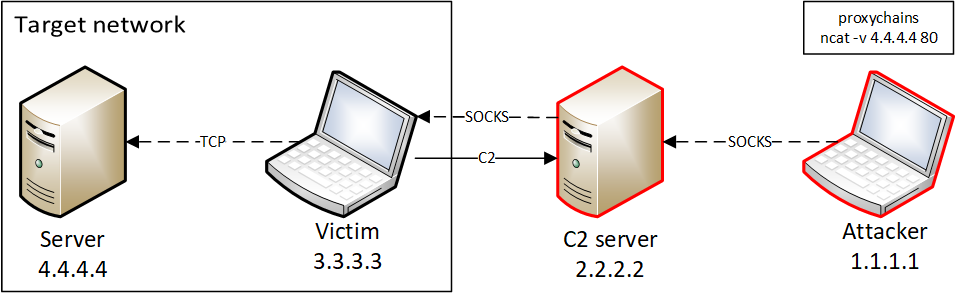

C2

Most C2 software has SOCKS functionality built-in. Once the SOCKS server is started, on the C2 server or on C2 client on the attacker’s system a SOCKS port is opened. From the attacker system it is then possible to use tooling over the SOCKS tunnel to connect to ports in the target network. This results in the C2 implant only being used as a OSI layer 4 router of network traffic and does not load and execute malicious code inside of its memory, leading to less activities that security software on the endpoint can trigger on. The following diagram illustrates how the C2 software on the Victim system connects to the C2 server and on the C2 server exposes a SOCKS port. Next, the Attacker can use proxychains-ng with netcat to instruct SOCKS to connect to a Server (4.4.4.4) in the target network on port 80/TCP. The SOCKS connection is then encapsulated in the C2 traffic and the Victim system running the (reverse) SOCKS server connects to the Server on port 80/TCP.

Besides using the built-in SOCKS functionality of C2 software there are also various other setups which allow access to the target network over SOCKS. These setups will be discussed in the following subsections.

SSH

The SSH client which is nowadays present on both Windows and Linux has SOCKS functionality built-in. Moreover, SSH can expose SOCKS on either the SSH client side or on the SSH server side.

When connecting over SSH to a remote (victim) host using the SSH client, the -D parameter can be provided with a port number to the SSH client, which then opens a SOCKS4a listener on the client host. For example, ssh 2.2.2.2 -D 1080 will connect to the SSH server running on port 22/TCP of 2.2.2.2, and then on the client (1.1.1.1) launch a SOCKS4a listener on the loopback interface on port 1080/TCP.

Alternatively, using the -R parameter an SSH connection can be established from the victim host (1.1.1.1) to the attacker’s SSH server (2.2.2.2), exposing the network to which the victim is connected on a SOCKS port on the attacker’s SSH server. The commandline for this setup is ssh 2.2.2.2 -R 1080. Once connected, the attacker’s SSH server will have a SOCKS4a listener on port 1080/TCP.

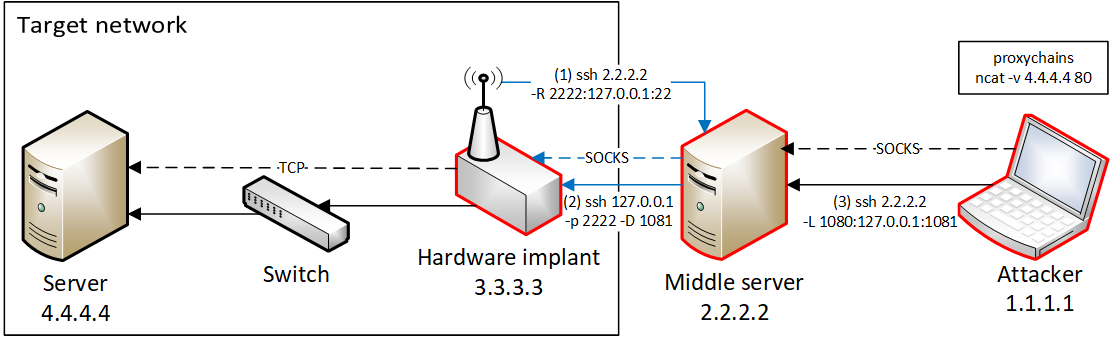

Hardware implant

A bit more complex setup could also be used during a red team with a hardware implant like a Raspberry Pi, which is for example connected to the network outlet in a meeting room. This hardware implant then automatically connects back over a 4G/5G dongle to an online hosted Linux middle server where in the connection the -R 2222:127.0.0.1:22 parameter to expose the SSH port of the hardware implant on the middle server. This then allows the attacker to connect to the middle server, and through port 2222 on this middle server get access to the hardware implant where again the -D parameter of the SSH client is used to launch the SOCKS server on the attacker side. This then provides the attacker access to the network where the hardware implant is connected. The blue lines in the schematic indicate that these connections are going over the 4G/5G dongle of the hardware implant.

Reverse SOCKS

Often as a red teamer though, access is obtained to a user endpoint which is not directly accessible from the Internet. In such case it is required that the compromised endpoint initiates a connection to an attacker-controlled server, which in turn enables tunneling SOCKS traffic over the compromised endpoint into the target network. Fortunately, such tooling exists, and examples of such tools are Chisel and gost. The diagram for reverse SOCKS looks similar to the one of C2, except that the protocol might differ compared to C2 in the sense that often a TCP connection is used which keeps connected whereas with C2 often a temporary HTTP connection is used which periodically checks whether there are any pending actions.

Chisel

Chisel6 is a great tool written by Jaime Pillora (@jpillora) in Go which consists of a client and server component and allows for reverse SOCKS connections which are tunneled over HTTP. In the Releases of the Chisel repository binaries are available for a variety of operating systems and architectures. Setting Chisel up is very straight forward.

- On an attacker-controlled server launch Chisel in server mode with the

--reverseflag where the port (1234) should be accessible from the victim system:chisel server -p 1234 --socks5 --reverse - On the victim system, execute Chisel in client mode where the IP address and port of the server are specified:

chisel client 2.2.2.2:1234 R:socks - Once the victim system is connected to the server, the server will open port

1080/TCPwhich allows incoming SOCKS5 connections

Note that at the moment of writing of this article, the implementation of SOCKS5 on jpillora’s GitHub does not yet support the UDP ASSOCIATE feature of SOCKS5. A fork7 and pull request8 created by the GitHub user Meteorite however does support this SOCKS5 feature. AMD64 Windows and Linux binaries (chisel64.exe and chisel64) can be built as follows:

git clone -b feature-socks-udp-associate https://github.com/Meteorite/chisel.git

cd chisel

GOOS=windows GOARCH=amd64 CGO_ENABLED=1 CC=x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc go build --buildmode=exe -ldflags="-s -w" -o chisel64.exe main.go

GOARCH=amd64 CGO_ENABLED=1 go build -ldflags="-w -s" -o chisel64 main.go

After building, chisel64 can be executed on the server whereas chisel64.exe can be used from the victim system.

Gost

Gost9 is a tool written by ginuerzh (@ginuerzh) which stands for GO Simple Tunnel and is often used to bypass the Great Firewall of China (GFW). Gost supports a myriad of protocols and transport types. Additionally, gost also supports spawning a SOCKS server and a reverse TCP port forward. Combining these two functionalities, it is possible to spawn a SOCKS server on the client (victim) system and then providing access to that SOCKS server through the reverse port forward. Because gost supports so many options, protocols and transport types it might initially be a challenge to setup, however it is useful to blend into other traffic. Like for Chisel, in the Releases of the gost repository binaries are available for a variety of operating systems and architectures.

Example of how to setup a reverse SOCKS tunnel over the ssh protocol:

- Launch the gost SSH server on an attacker-controlled server where the port (

1234) should be accessible by the victim system:gost -L=sshd://:1234 - Launch the SOCKS server and reverse port forward on the client (victim) system:

gost.exe -L=socks5://127.0.0.1:4321 -- -L=rtcp://:1080/127.0.0.1:4321 -F=sshd://1.1.1.1:1234 - Once the victim system is connected to the server, the server will open port

1080/TCPwhich allows incoming SOCKS5 connections

Something to be aware of is that there are two different versions of gost: v2 which is the legacy version, and v3 which is the version that is rebuilt from scratch. The above commands are valid for v3 and have not been tested on v2. See below a table with links of the two versions.

| Version | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

| GitHub | https://github.com/ginuerzh/gost | https://github.com/go-gost/gost |

| Download | https://github.com/ginuerzh/gost/releases | https://github.com/go-gost/gost/releases |

| Documentation | https://v2.gost.run/en/ | https://latest.gost.run/en/ |

| Notes | Legacy version of Gost |

Other options

Besides reverse SOCKS servers there are also other situations in which socks can be used.

Consider for example the SocksOverRDP10 tool written by Balazs Bucsay (@xoreipeip) which adds a module to the RDP (mstsc.exe) or Citrix client on the attacker side. After launching the SocksOverRDP server component on the RDP/Citrix server side, the RDP/Citrix client opens up a SOCKS port through which the network in which the RDP/Citrix server resides can be accessed over SOCKS.

Another example is a tool called pivotnacci11 written by Eloy Pérez (@Zer1t0) which can be used to pivot over a compromised webserver into the network in which the webserver is located. The tools consist of a script (.aspx, .jsp or .php) which is placed on the webserver and a Python script which is executed on the attacker side, connects to the webserver. Once connected to the webserver, the Python script locally opens up a SOCKS port which can be used to pivot into the network in which the webserver resides.

Many more tools are available which are available which offer some kind of SOCKS support. Aspects to consider when looking for tools are:

- Support for reverse a reverse SOCKS connection: When launched on the victim system, it connects back to the attacker, and then opens a SOCKS listener on the attacker system providing access to the network the victim system is connected to;

- Support for outgoing proxy: Regularly corporate environments restrict the ports. This usually means systems are able to connect to just the web ports (

80,443) and in addition require clients to go over an outgoing proxy server to access the Internet; - Support for proxy authentication: In case a proxy is required to access the Internet, some might also require some type of authentication like basic, NTLM or Kerberos. In case the SOCKS software uses the winhttp.dll library, going over the proxy and if needed authenticating to it is handled transparently. If that library is not used, the proxy server address and credentials might have to be specified explicitly. Generally, C2 software under the hood takes care of any corporate proxy that might be in place, which is then also used transparently when the SOCKS functionality of the software implant is activated;

- Optionally: Type of SOCKS that is supported and which features of the protocol are implemented: Most tools support SOCKS4A, various tools also SOCKS5, but only a few of the tools supporting SOCKS5 also implement the UDP ASSOCIATE feature.

The list of tools that I have taken a look at can be found in Appendix A: Comparison of SOCKS tools.

Summary

The table below shows the summary of the SOCKS setups that have been discussed in this section.

| Title | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| C2 | C2 software implants often have SOCKS functionality built in. | https://www.thec2matrix.com/ |

| Linux | SOCKS tunnel by either directly connecting to a Linux server using the SSH client using the -D parameter, or alternatively by placing a hardware implant in the target network which dials back to a middle server and then provides SSH access to the hardware implant. |

n/a |

| Chisel | Tunneling tool which natively supports reverse SOCKS and provides binaries for many platforms and architectures. Meteorite’s fork provides support for the SOCKS5 UDP ASSOCIATE feature. | https://github.com/jpillora/chisel |

| gost | Advanced tunneling tool which allows to tunnel over a myriad of protocols, supporting SOCKS and (via rtcp) reverse SOCKS. Provides binaries for various platforms and architectures. | https://github.com/go-gost/gost |

| SocksOverRDP | SOCKS tunnel over dynamic virtual channels of Microsoft Remote Desktop or Citrix Remote Desktop. | https://github.com/nccgroup/SocksOverRDP |

| pivotnacci | SOCKS tunnel over compromised webserver (.aspx / .php / .jsp) |

https://github.com/blackarrowsec/pivotnacci |

Windows, red teaming and SOCKS

Thinking of an attacker machine, people usually immediately think of a Linux system with a distribution like Kali or BlackArch with a large number of hacking tools and scripts12,13. What many do not realize however is that for attacking Windows-based environments, Windows through its various PowerShell modules and binaries is a great offensive operating system which is very capable of performing a whole range of offensive actions against remote Windows systems and services.

Advantages of using Windows

While performing a red team, the operator effectively is a system administrator who is managing someone else’s environment. Having all Windows’ management tooling at your disposal together with some kind of credential material which authorizes you to interact with the environment is generally all that is needed to perform the job.

Activities that can be performed from Windows are plentiful, a number of examples:

- Enumerating and modifying Active Directory;

- Interacting with remote systems performing reconnaissance on active sessions, system information, running processes;

- Modifying a remote system’s configuration through the registry or Microsoft’s (sometimes undocumented) protocols used by the various Microsoft Management Console (MMC) snap-ins;

- Execution of commands on remote systems through the various options that are available on Windows.

Having the capability to perform such activities from an Offensive Windows machine over SOCKS has various advantages.

- No execution takes place on the victim system in the target network, where activities could be picked up by the security software;

- Instead of just shooting with offensive tools at an environment, you are learning the sysadmin (engineering) side of the story; literally using the tools the administrators use to manage the remote network;

- Windows regularly makes use of undocumented protocols for which no open source (Linux-based) tooling/scripts might have been written yet while Windows natively speaks with other Windows systems. This means that Windows functionalities can directly be used from an attacker Windows.

- Kerberos is natively used whenever an authentication is requested by a remote system - more on this in the upcoming sections;

- It is possible to install any Windows-based 3rd party software that is used in the target network on the Offensive Windows machine and use it over the network. Moreover, it is possible to copy Windows-based software that has been in-house developed by the target organization to the Offensive Windows machine and use it from there as well;

- While network security sensors might trigger on Linux tools like the Impacket implementations of certain protocols, it is less likely that it will trigger when using Windows’ built-in functionality and protocol implementations;

- When accessing webpages in the target organization, an actual Windows-based browser like Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome is being used, instead of spoofing the user agent, but leaving many other possible traces that the browser was running on a Linux machine.

SOCKS tooling in Windows

When searching online, there are various tools for Windows like Sockscap6414, ProxyCap15 and Proxifier16 which “socksify” applications to force applications that are not SOCKS aware over the SOCKS tunnel. These tools work well for applications like browsers and other tooling that simply establish connections, however lower-level communication and communications initiated by for example out-of-process COM objects are not properly proxied. Moreover, in case any issues arise, it is hard to look into the traffic that is send over SOCKS and debug what is going wrong. Finally, it might be hard to be selective on the traffic that should end up in the target environment as like with proxychains-ng by default connections established by the socksified application are forced over the SOCKS tunnel.

Disadvantages of using SOCKS

In addition to the challenges using tools to socksify applications in Windows, SOCKS also does have a number challenges to be aware of.

- First of all, for SOCKS to work, it requires a real-time interaction between the attacker and the victim system. If the SOCKS traffic is going over a C2 protocol like HTTP which is the default for many C2 frameworks, this will be very noisy on the compromised system and possibly in-between outgoing proxy or network monitoring solutions. Fortunately nowadays connections like WebSockets or other streaming protocols are very common nowadays, so a(n additional) C2 channel which uses such protocol can be established and then used for SOCKS. Alternatively, as discussed in the previous section there are various tools which are able to blend in well with the traffic.

- Depending on the tool and protocol that is used to communicate to the remote system, it might be very slow. For example, when listing the services that are installed on a remote system, for every service four requests are performed which leads to quite some round trips with the number of services that are nowadays installed on a Windows system.

- As opposed to a software implant which runs under the context of a certain user and will use that user’s credential material when challenged, SOCKS is only working on the network. For that reason, in case a remote system performs a challenge for authentication, the Offensive Windows machine needs to have credential material ready to authenticate whereas if a tool would be executing on the victim system, the authentication would probably be transparently taken care of. More on how to tackle this in the upcoming sections.

The upcoming sections deal with the issue that it is hard to route Windows traffic over SOCKS. The subsequent section will go into detail on how to resolve the challenge of authenticating from the Offensive Windows machine.

A match made in heaven

What if, instead of trying to force Windows to perform its activities over SOCKS, we combine the strengths of the Linux and Windows operating systems? Linux is great at low-level network manipulation while the Windows operating system is great for interacting with remote Windows systems. If through some network configuration it is possible to convince Windows that is able to directly reach the network segments that are reachable from the victim host, Windows is much more willing to collaborate.

To fool Windows, several years ago I started using a solution which consisted of having both a Linux and Windows VM where on the Linux VM I launched several socat17 forwarders in parallel, but through proxychains-ng. This looked as follows:

proxychains socat TCP-LISTEN:445,fork TCP:4.4.4.4:445

proxychains socat TCP-LISTEN:5985,fork TCP:4.4.4.4:5985

In my Windows VM I then added a new entry to the hosts file which made target.victim.com point to the IP address of my Linux VM. After setting that up, it was possible to instruct Windows to for example list the network shares of target.victim.com, which would then be natively performed from the Windows VM against the Linux VM. In turn the Linux VM would just forward the traffic over SOCKS to the remote host and send back any responses to the Windows VM.

The problem of this setup however is that is not scalable. Whenever a different host needs to be accessed on the same port, the socat listeners on the Linux VM need to be taken offline and new listeners need to be launched. Moreover, additional entries needed to be added to the Windows hosts file to point the hostnames in the target network to the IP address of the Linux VM.

At some moment however I discovered the badvpn software18 by Ambroz Bizjak which contains the tun2socks utility. This utility is able to use a newly created tun interface in Linux, and then tunnel any incoming packets over a SOCKS server to the target network, which is exactly what I needed! As nowadays the badvpn project is no longer maintained an excellent replacement is the tun2socks19 utility by Jason Lyu (@xjasonlyu) which is regularly updated and at the Releases page provides compiled versions for various operating systems and architectures.

Combining tun2socks with the power of Linux’ iptables, routes and DNS server, it provides the perfect setup for Windows to be used as an offensive platform! In the remainder of the article, it is assumed a SOCKS server is used which does not support the UDP ASSOCIATE feature, which is currently the case in most implementations. In case this feature is supported, it simplifies the setup some aspects.

On a high level, this setup on the Linux routing VM is as follows:

- The Offensive Windows VM is placed behind the Linux routing VM, so Linux is able to control all of the traffic coming from the Offensive Windows VM;

- The tun2socks network interface is created and configured to reach the target network over SOCKS;

- Using iptables rules split tunneling is configured where by default all traffic is routed to the Internet while routes for specific subnets are configured to go over the tun2socks interface;

- A DNS server (dnsmasq) is installed and configured on Linux and the Offensive Windows VM is configured to use this DNS server. This makes sure DNS requests destined for the client network are sent there while everything else is sent to the default Internet DNS server;

- Some fix-ups are put in place to make sure everything works smoothly.

An additional benefit of this setup is that by default Windows is pretty chatty on the local network segment. Because this network is only between the Linux routing VM and Offensive Windows VM, it does not matter how much noise Windows is making as besides the Linux routing VM who ignores it, nobody is listening anyway.

The next sections will discuss the setup of the Linux routing VM in detail whereas the Offensive Windows VM will be discussed in part 2 of this article.

Offensive setup: Linux routing VM

The following subsections discuss the different steps to set up the Linux routing VM. Personally, for the Linux routing VM I use the Arch Linux operating system linked to the BlackArch repository, but any Linux operating system will work fine.

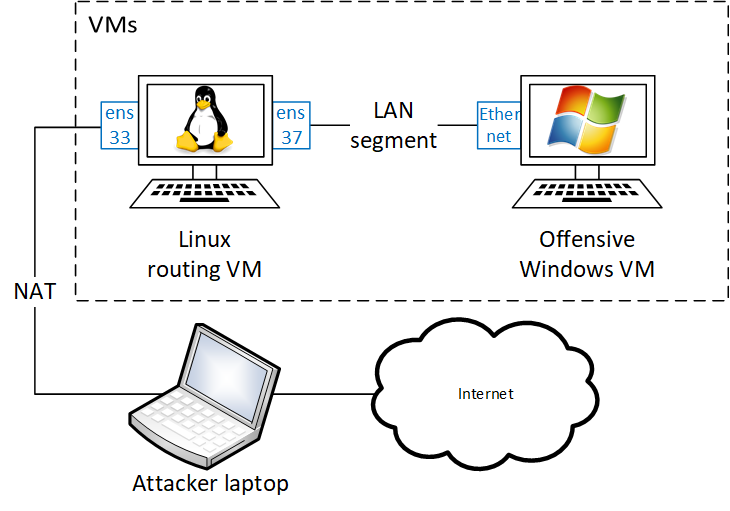

Two network interfaces

To start, the Linux routing VM requires two network interfaces. The first interface (ens33) is used to connect the Linux routing VM to the Internet. The second interface (ens37) is used for an internal network between the Linux and Windows VMs. In my setup I am using VMware Workstation where for the connection between the Linux and Windows VMs I simply create a new LAN segment and then connect both the second interface of the Linux routing VM as well as the interface of the Offensive Windows VM to it.

This second interface needs to be assigned a static IP address. In this article the IP address will be 10.120.0.1/24, however whenever there are more insights on what the target’s IP network segment IP addresses are, this IP and subnet size can be updated to blend in better with the client network. This is needed because in some occasions the internal IP address of the attacker Windows host (yes, you read that correctly, its internal IP) is being logged. Be aware though that the network segment that is used between the Linux and Windows VMs is not routable towards the target network.

To allow Linux to be able to forward traffic between its different network interfaces, configure the ip_forward flag as follows. This setting can also be set permanently by placing it in the sysctl.conf file. Once configured, the setting can be validated using cat /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward.

sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

DNS server

In the offensive setup, a split DNS setup is used. Moreover, optionally a DHCP server on the second Linux network interface can be configured to automatically assign an IP to the Offensive Windows VM(s) that are connected through that interface. For this purpose the dnsmasq20 DNS server software is used which can be installed through the Linux package manager. Next, the configuration can be updated in the /etc/dnsmasq.conf file as follows where the various target network DNS servers can be collected through the C2 software implant.

# Port

port=5353

# DHCP server

dhcp-range=10.120.0.100,10.120.0.200,12h

dhcp-option=option:dns-server,10.120.0.1

dhcp-authoritative

# Target network DNS server(s)

server=/ad.bitsadmin.com/10.0.10.10

server=/ad.bitsadmin.com/10.0.10.11

server=/10.0.10.in-addr.arpa/10.0.10.10

server=/10.0.10.in-addr.arpa/10.0.10.11

server=/corp.int/10.0.20.10

server=/20.0.10.in-addr.arpa/10.0.20.10

server=/research.dev/10.0.30.10

server=/30.0.10.in-addr.arpa/10.0.30.10

# Default DNS server

server=1.0.0.1

The configuration starts with setting the port of the DNS server to 5353. The reason why this is done is explained in the next heading.

Next, the configuration of the DHCP server which serves IP addresses in the range of 10.120.0.100 to 10.120.0.200 and a lease time of 12 hours where the DNS server is set to the IP address of the Linux routing VM. Next the domains (ad.bitsadmin.com, corp.int and research.dev) of the target network are defined where the DNS server IP addresses responsible for the ad.bitsadmin.com domain are set to 10.0.10.10 and 10.0.10.11 meaning that whenever a request comes in for whatever.ad.bitsadmin.com, one of these two IPs is queried to resolve the name.

The lines with in-addr.arpa are not required, but used for reverse DNS lookups which can be relevant when performing reconnaissance over DNS. This line states that whenever a reverse lookup is performed for an IP address starting with 10.0.10.x (or 10.0.20.x/10.0.30.x for respectively corp.int and research.dev) the IP address specified of the end of the line is used to perform the reverse lookup.

Finally, the default DNS server is specified, which in this case is set to the Cloudflare DNS server, but can be any public DNS server. This configuration makes sure that only specific requests end up at the DNS servers of the target network while others all end up at the public DNS server and therefore will not be visible in the target network. This is needed because when for example launching Burp, DNS requests to portswigger.net by Burp’s updater will be made to the DNS server in the target network which might trigger alerts with the SOC team. With this setup such requests will simply be sent to the Cloudflare DNS server.

Whenever during the engagement additional domains are discovered, these can also be added to this file. Make sure to restart the dnsmasq service after updating the configuration file to have the changes applied.

DNS server and UDP over SOCKS

As discussed before, many implementations of SOCKS server do not support the UDP ASSOCIATE functionality meaning that it is not possible to tunnel UDP traffic over the SOCKS tunnel. Fortunately, there is a solution for this. Even though by default for DNS port 53/UDP is used, the DNS specification states that larger requests/responses can also be performed over 53/TCP, which is supported by the SOCKS tunnel.

To make this all work, the dns_over_tcp.py script from the LOFL repository4 is available which does the following: Upon start of the script, the script initiates listeners on both port 53/UDP and port 53/TCP. This is also the reason why the dnsmasq DNS server should listen on port 5353, otherwise port 53 is already in use. Moreover, the dns_over_tcp.py script parses the /etc/dnsmasq.conf configuration file where based on the configured entries, the domains are selected for which the incoming DNS requests need to be converted to a DNS request over TCP.

Whenever dns_over_tcp.py receives a DNS request on port 53/UDP, it will check the record that is requested. In case the record matches the domains specified in the dnsmasq config parsed earlier, a DNS request over TCP is forged and it is sent to port 5353/TCP of the dnsmasq DNS server (127.0.0.1:5353). Because dnsmasq receives the request on its TCP port, its behavior is to then also interacts over TCP with the server that is configured for that domain, which solves the problem of the unsupported UDP protocol. The answer from the target network’s DNS server is then sent over TCP from dnsmasq back to the dns_over_tcp.py script which simply responds again over UDP to the client performing the DNS request.

Whenever the dns_over_tcp.py script receives a DNS request on port 53/UDP which does not match a domain in the dnsmasq config, it connects over UDP to port 5353 of dnsmasq. Because the incoming request was over UDP, dnsmasq then simply uses UDP to connect to the default DNS server (1.0.0.1) and provides back the response to the dns_over_tcp.py script which is then returned to the client performing the DNS request.

Once dnsmasq has been configured and the dns_over_tcp.py script is running, also the nameserver of the Linux routing VM can be set to itself by executing the following commands where the second command is optional to lock the /etc/resolv.conf file for modifications.

echo nameserver 127.0.0.1 > /etc/resolv.conf

chattr +i /etc/resolv.conf

Tun2socks

Once a SOCKS port is listening which provides access to the target network, tun2socks needs to be configured. As described in the A match made in heaven section, Linux binaries for tun2socks can be obtained from the tun2socks GitHub19.

The tun2socks utility requires a new tunnel adapter to be set up. This can be done using the following commands.

ip tuntap add mode tun dev tun1

ip addr add 198.18.0.1/15 dev tun1

ip link set dev tun1 up

Using these commands, a new tunnel interface called tun1 is created. Next, an IP address is assigned to the newly created interface. This IP address is part of an address block which is reserved for benchmarking, and it is therefore safe to assume it will not be used by the target network. Finally, the tun1 interface is brought online. At the LOFL repository4 a utility called create_tun.sh is available which performs this actions automatically. See the command-line parameters that can be used below.

Create Tunnel Interface v1.0

@bitsadmin - https://github.com/bitsadmin/lofl

Usage: create_tun.sh [-d] INTERFACE [IPSUBNET]

Parameters:

-d: Delete the interface

INTERFACE: Name of the interface to be created, for example tun1

IPSUBNET: IP address and subnet mask that will be assigned to the new interface.

Noted down in CIDR notation, for example: 198.18.0.1/15

Examples:

Create new tunnel interface tun1

create_tun.sh tun1

Create new tunnel interface tun1 with specific IP/subnet

create_tun.sh tun1 198.18.0.1/15

Delete tunnel interface tun1

create_tun.sh -d tun1

After creating the tun1 interface, the tun2socks command line can be used to link the interface to the SOCKS server and have all traffic sent to the tun1 interface forwarded over the SOCKS tunnel. This command-line looks as follows.

tun2socks -device tun1 -proxy socks4://127.0.0.1:1080

As can be seen, the -device parameter specifies the interface it should use to receive traffic, which is then forwarded over SOCKS. The -proxy parameter specifies where the traffic coming in at the device should be proxied to. The proxy protocol (in this case socks4) has various options where for LOFL the relevant options are either socks4 or socks5. More options for the proxy protocol can be found at the Proxy Models page in the tun2socks wiki21.

The tun1 interface is now available to get traffic into the target network, however two more settings need to be configured before it can be used.

Routes

Currently because there are no routes configured to the tun1 interface yet, no traffic will be sent yet over this interface and instead everything will be sent over the default route. Such setup is good, because like with the split DNS setup, for OPSEC purposes it is important that only the relevant traffic is routed to the target network.

Based on the IP configuration of the victim system which is used for the SOCKS pivoting and any reconnaissance that has been performed on the setup of the domain, IP addresses can be added to the routing table. Proceeding with the example of the ad.bitsadmin.com lab, the following IP ranges can be added to be routed over the SOCKS tunnel on tun1.

# IP range of ad.bitsadmin.com

ip route add 10.0.10.0/24 via 198.18.0.1 dev tun1

# IP range of corp.int

ip route add 10.0.20.0/24 via 198.18.0.1 dev tun1

# IP range of research.dev

ip route add 10.0.30.0/24 via 198.18.0.1 dev tun1

Alternatively, in the LOFL repository the add_routes.sh utility is available which aids in creating the routes.

Usage: add_routes.sh <subnet_file> <interface> [gateway_ip]

At this point, from the Linux routing VM it is now possible to connect to systems on the target network. One more step is still required though to also provide the Offensive Windows VM possibility to reach the target network.

Iptables

Because the Offensive Windows VM is in a different network segment, a network address translation (NAT) configuration is required for the Linux routing VM to properly masquerade traffic originating from the Offensive Windows VM. That way the Offensive Windows VM is able to send traffic to its default gateway (the Linux routing VM), which is then routed accordingly to the appropriate gateways which are either the Internet (default) or the specific target network subnets which are configured in the previous subsection. The following commands can be used for this.

# Internet

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o ens33 -j MASQUERADE

iptables -A FORWARD -i ens33 -o en37 -m state --state RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

iptables -A FORWARD -i en37 -o ens33 -j ACCEPT

# Target network

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o tun1 -j MASQUERADE

iptables -A FORWARD -i tun1 -o en37 -m state --state RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

iptables -A FORWARD -i en37 -o tun1 -j ACCEPT

Alternatively, in the LOFL repository the utility iptables_nat.sh is available which aids in creating the iptables NAT rules.

Create iptables NAT v1.0

@bitsadmin - https://github.com/bitsadmin/lofl

Usage: iptables_nat.sh [-d] [-f] INPUT OUTPUT

Parameters:

-d: Delete the iptables rule

-f: Skip user confirmation prompt

INPUT: Input interface

OUTPUT: Output interface

Examples:

Create NAT from ens36 to tun1

iptables_nat.sh ens36 tun1

Delete NAT from ens36 to tun1

iptables_nat.sh -d ens36 tun1

Delete NAT from ens36 to tun1 without prompt

iptables_nat.sh -d -f ens36 tun1

Because split tunneling is used, the iptables rules need to be configured for both the ens37 to ens33 (default gateway) interfaces and for the ens37 to tun1 (target network) interfaces.

Network traffic logging

During pentesting and red teaming activities a best practice is to maintain logging of interactions with the client environment, such as the network traffic. The LOFL setup allows for a very easy logging of such network traffic by simply running a tcpdump on the tun1 interface. Such command looks as follows.

tcpdump -s0 -n -i tun1 -w $(date +%Y%m%d%H%M%S).pcap

Conclusion

After all steps have been performed, on the Linux host it is now possible to interact with the target network as if it is a locally connected network. This can for example be validated by resolving the DNS A records of the domain.

host -t A ad.bitsadmin.com

This concludes the setup of the Linux routing VM to facilitate for the living off the foreign land activities performed from the Offensive Windows VM. In part 2 of this article, the configuration of the Offensive Windows VM will be discussed. Moreover, this second part will detail the various ways of collecting different types of credentials from the victim system and how to use them from the Offensive Windows VM.

Troubleshooting

Network does not seem to work

Launch Wireshark on the Linux router VM and individually check the traffic going over the SOCKS tunnel (tun1) as well as the traffic between the Linux router VM and the Offensive Windows VM (ens37). Examples of issues that can surface here are:

- In case no traffic is observed on tun1, the Linux routing VM might not be correctly configured

- Check that the

ip_forwardflag of the OS is set to true:cat /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward - Check that the iptables are configured correctly:

iptables -nvL - Check that relevant routes exist:

ip route | grep tun1 - Make sure that tun2socks is running, not reporting errors and the correct

-deviceand-proxyparameters are specified

- Check that the

- In case no responses are observed to TCP packets sent over

tun1, validate that the SOCKS server is running properly

DNS records do not resolve

- If the

/etc/dnsmasq.confhas just been modified, make sure to restart both thednsmasqservice and thedns_over_tcp.pyscript to apply the changes - Make sure the

dns_over_tcp.pyscript is running and not reporting errors - More debugging can be performed using the

digutility, forcing the queries to go over TCP to test the various links in the chain

# Check whether dns_over_tcp.py works

dig @127.0.0.1 -p 53 ad.bitadmin.com +retry=0 +tcp

# If not, check whether dnsmasq works

dig @127.0.0.1 -p 5353 ad.bitadmin.com +retry=0 +tcp

# If not, check whether directly querying the DC IP over TCP works

dig @10.0.0.10 -p 53 ad.bitadmin.com +retry=0 +tcp

Port does not respond

Be aware that the tun2socks software is a bit deceptive. For performance reasons when a TCP SYN packet is sent to the tun2socks interface (tun1), the interface immediately responds with a SYN/ACK response without checking whether the port on the target is actually open. For that reason make sure to check the output of tun2socks to see whether a warning is displayed for the host:port combination the connection is attempted to. Alternatively using proxychains (make sure the correct SOCKS server/version is set in /etc/proxychains.conf) it is possible to validate using for example ncat or nmap -sT whether a port is open. See also the Future work on a possible fix for this.

CLDAP queries are not properly forwarded

It is a known issue that for some reason the cldaproxy.sh script is not always working properly. In case a LOLFCAB hangs and and by looking at the network traffic between the Offensive Windows VM and the Linux routing VM it shows that CLDAP (389/UDP) is used, restarting the cldaproxy.sh script might resolve the issue.

Windows Terminal does not accept input

When launching Windows Terminal (wt.exe) from an elevated prompt in which the credential material has been prepared, it is not possible to use the keyboard input. This is a known issue with Windows Terminal, for more information see https://github.com/microsoft/terminal/issues/9971.

Appendix A: Comparison of SOCKS tools

| Type | Title | Native reverse? | UDP | Proxy support/auth | Website | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2 | Cobalt Strike | Yes | No | Yes, transparent | https://www.cobaltstrike.com/ | Documentation: https://hstechdocs.helpsystems.com/manuals/cobaltstrike/current/userguide/content/topics/pivoting_socks-proxy.htm |

| C2 | Metasploit | Yes | No | Yes, transparent | https://www.metasploit.com/ | Documentation: https://www.rapid7.com/db/modules/auxiliary/server/socks4a/ |

| C2 | Sliver | Yes | ? | Yes, transparent | https://github.com/BishopFox/sliver | Documentation: https://github.com/BishopFox/sliver/wiki/Reverse-SOCKS |

| C2 | * | n/a | n/a | n/a | https://www.thec2matrix.com/ | Website dedicated to comparing many different C2 frameworks, including whether they have SOCKS support |

| Hardware | Hardware implant | No | No | n/a | n/a | Connecting to hardware implant or a Linux server and specifying the dynamic port forwarding flag (-D): ssh -D 1080 or reverse dynamic port forwarding flag (-R): ssh -R 1080 |

| RDP | Ica2Tcp | n/a | No | n/a | https://github.com/synacktiv/ica2tcp | For Citrix |

| RDP | rdp2tcp | n/a | No | n/a | https://github.com/V-E-O/rdp2tcp | For rdesktop in Linux |

| RDP | SocksOverRDP | n/a | No | n/a | https://github.com/nccgroup/SocksOverRDP | SOCKS tunnel over dynamic virtual channels of Microsoft Remote Desktop or Citrix Remote Desktop |

| RDP | UniversalDVC | n/a | No | n/a | https://github.com/earthquake/UniversalDVC | |

| RDP | xfreerdp | n/a | No | n/a | https://github.com/FreeRDP/FreeRDP | |

| Script | Invoke-SocksProxy | Yes | No | Yes, transparent | https://github.com/p3nt4/Invoke-SocksProxy | Great script, but in very early beta. Works well from PowerShell core, not from Windows PowerShell |

| Tool | chisel | Yes | Yes* | Yes, not sure which auth | https://github.com/jpillora/chisel | * Supports UDP when using the following fork: https://github.com/Meteorite/chisel/tree/feature-socks-udp-associate |

| Tool | fullproxy | Yes | No | No | https://github.com/shoriwe/fullproxy | |

| Tool | gost | No | ? | Yes, basic | https://github.com/go-gost/gost | |

| Tool | Lastenzug | No | No | ? | https://github.com/codewhitesec/Lastenzug | Implements a Socka4a proxy based on WebSockets |

| Tool | MicroSocks | No | No | n/a | https://github.com/rofl0r/microsocks | Linux-only |

| Tool | penguin | No | No | Yes, basic/? | https://github.com/myzhang1029/penguin-rs | |

| Tool | revsocks | Yes | No | Yes, basic/NTLM | https://github.com/kost/revsocks | |

| Webserver | Pivotnacci | n/a | No | n/a | https://github.com/blackarrowsec/pivotnacci |

References

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 1/3: Setup Linux VM for SOCKS routing

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 2/3: Configuring the Offensive Windows VM

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 3/3: Using Windows as Offensive Platform

- Digging for Secrets on Corporate Shares

- Dealing with large BloodHound datasets