Dealing with large BloodHound datasets

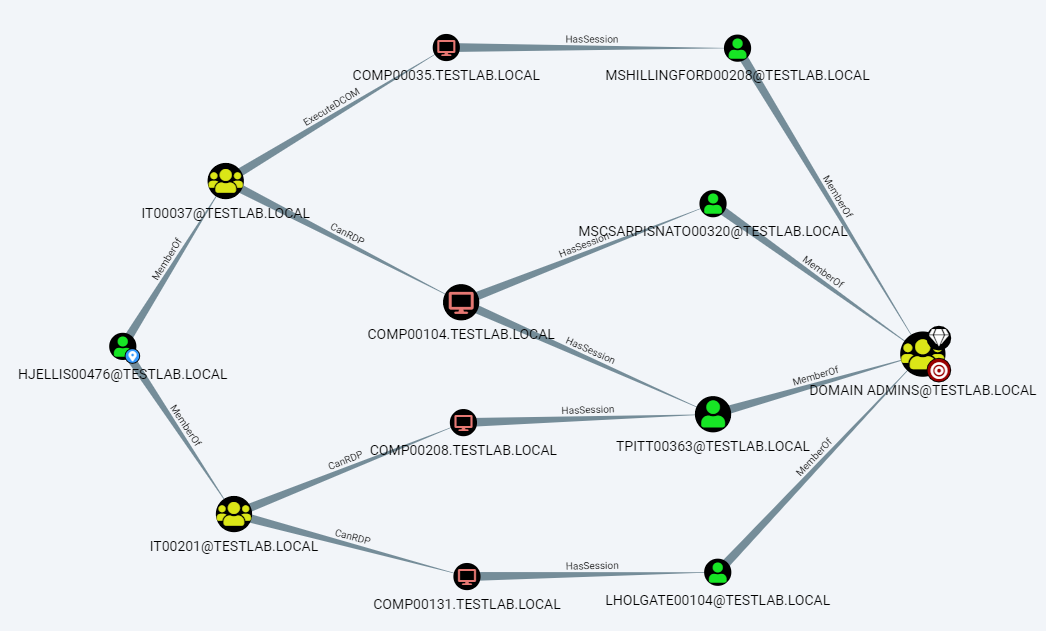

On a regular basis I am involved in assignments in which a security analysis of an Active Directory has to be performed. To perform such assessment, a variety of tools is used of which one is BloodHound. The power of BloodHound is that it represents the various objects in Active Directory as nodes (e.g., users, computers, GPOs) and the relations between those objects as edges (e.g., MemberOf, Owns, CanRDP). Using queries it is possible to quickly identify potential escalation paths and also visualize them in an understandable way.

In this article I describe some of my experiences using BloodHound, including the challenges I ran into when trying to import large datasets. I also provide alternative ways to query the BloodHound database so depending on the scenario, different types of data can be extracted for further analysis and reporting. I hope this post provides some new insights that you can use to your advantage.

Description of BloodHound from the GitHub page1:

BloodHound uses graph theory to reveal the hidden and often unintended relationships within an Active Directory or Azure environment. Attackers can use BloodHound to easily identify highly complex attack paths that would otherwise be impossible to quickly identify. Defenders can use BloodHound to identify and eliminate those same attack paths. Both blue and red teams can use BloodHound to easily gain a deeper understanding of privilege relationships in an Active Directory or Azure environment.

Nowadays BloodHound supports both Active Directory and Azure AD resources. This article is focused on the Active Directory functionality, although parts of it (like querying) are probably also relevant to the data collected from Azure.

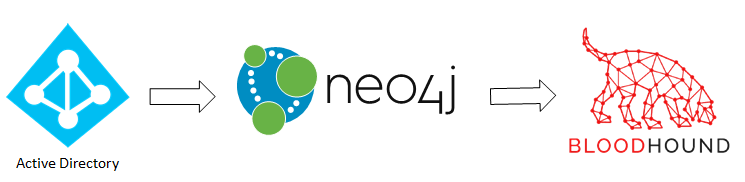

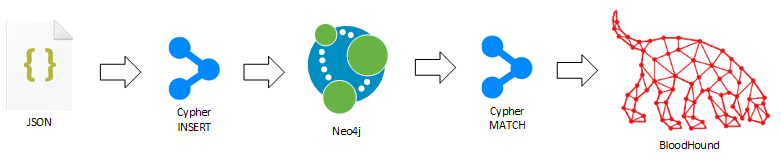

The process of using BloodHound is to first collect data from Active Directory’s LDAP servers using SharpHound (or the Azure APIs in case of AzureHound) and store it in JSON files that are zipped to reduce the file size. Next, these files can be moved to the system at which the analysis will take place and imported into a Neo4j database. Finally, queries can be performed, either using the BloodHound tool, other 3rd party tools or directly using Neo4j’s Cypher language. In this article we will go through these three stages.

Collection

The main tool provided with BloodHound for collecting information from Active Directory is SharpHound. SharpHound is a .NET 4 executable that has several parameters to configure which data needs to be collected. These parameters influence the amount of data collected and stealthiness of execution. SharpHound will then collect information from LDAP/LDAPS from a Domain Controller. Moreover, depending on the enumeration flags specified, it will also connect to individual hosts through RPC over a named pipe (ncacn_np) which takes place over the Microsoft-DS (445/TCP) port to get information about local group membership and logged on users.

Besides the SharpHound tool, there are several other options to collect data as listed in the table below:

| Tool | Language | Url | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SharpHound | .NET 4 executable | https://github.com/BloodHoundAD/SharpHound/ | Also possible to be executed in-memory using Cobalt Strike, check @william_knows’ blog post |

| AzureHound | PowerShell | https://github.com/BloodHoundAD/AzureHound/ | Specifically for Azure environments, outside of the scope of this article |

| SharpHound.ps1 | PowerShell | https://github.com/BloodHoundAD/BloodHound/ | Available from the Collectors folder. Using PowerShell reflectively loads the embedded SharpHound.exe .NET executable. It exposes the Invoke-BloodHound function which calls the main function of the SharpHound binary. |

| SharpHound.py | Python | https://github.com/fox-it/BloodHound.py/ | Python version of SharpHound |

| ADExplorerSnapshot.py | Python | https://github.com/c3c/ADExplorerSnapshot.py/ | Convert Sysinternals ADExplorer snapshots to BloodHound-compatible JSON files. |

| BOFHound | Python | https://github.com/fortalice/bofhound/ | Generate BloodHound compatible JSON from logs written by ldapsearch BOF and pyldapsearch. |

After collecting the necessary input files, we can move on to the next step: importing the files to BloodHound.

In case you do not have an Active Directory dump available but still would like to play with Cypher queries (discussed in the Querying section), you can also load some dummy data into BloodHound using the DBCreator.py tool, which can be installed as follows:

git clone https://github.com/BloodHoundAD/BloodHound-Tools/

cd BloodHound-Tools/DBCreator

pip install -r requirements.txt

Once installed, the script can simply be launched to open an interactive prompt. In the prompt the dbconfig command can be used to interactively configure the URI, username and password of your Neo4j instance. After this configuration, connect to the database using the connect command and have the dummy data generated and inserted using the generate command. Once done, you can skip the Importing section and immediately check out the Querying section.

Importing

After setting up BloodHound with the Neo4j graph database back-end as described in the Installation section at https://bloodhound.readthedocs.io/, the collected data can be imported.

The usual way of importing is to simply launch the BloodHound GUI and drag the JSON and/or zip files over the main application window. Alternatively the Import button on the right can be used to select the files you want to import.

During the import process, BloodHound reads the JSON and translates those into Cypher CREATE statements which create the various nodes and edges in the Neo4j graph database. The nodes represent objects like Computers, Users, Groups, GPOs, etc. with their respective attributes while the edges represent the relations like MemberOf, Owns, WriteDacl, CanRDP, etc.

The import usually works well, however sometimes it fails. In that case a solution can be to try out a different version of BloodHound which sometimes somehow magically solves the import problems. These BloodHound versions can also perfectly be installed side-by-side. If the files still fail to import, it could be that there is some other issue.

Recently I was working on an assignment where I had to analyze a very large Active Directory environment. During the assignment, BloodHound files were provided to me and while some imported without any problems, others simply did not import without giving any feedback or error message on what went wrong. In the next sections I will discuss the steps I went through to resolve these issues.

Large files

My first attempt to solve the import issue, was to use the bloodhound-importer.py script2, however it turned out that only the BloodHound v3 data format is currently supported while the dumps I receive were apparently of version 4 format. As later turned out, the file format does not differ much, but at that moment I decided to split up the file using some lines of PowerShell.

I went ahead and used PowerShell’s Get-Content/ConvertFrom-Json to read the JSON data and split up a 250MB JSON file. The structure of the BloodHound v4 JSON file is as follows:

{

"data": [

"ChildObjects": [

{

...

},

{

...

}

],

"Trusts": [

{

...

}

]

],

"meta": {

"methods": 29695,

"type": "domains",

"count": 3,

"version": 4

}

}

The script executed without any issues and the resulting files looked good containing the number of entries I specified to collect and an updated meta section with the correct number of items. However, when importing the file into BloodHound, it reported that the file was created using an incompatible collector, which seemed odd. After debugging for a while, I figured out that it is required to put the meta section at the end of the file while I placed it at the front of the file. After putting the section at the end of the file, BloodHound imported the data well.

Next, I executed the script against a 4GB JSON file however despite of the 64GB of RAM in my system, PowerShell almost immediately quit the script with the exception Insufficient memory to continue the execution of the program. This makes sense because when the file is loaded into memory and parsed as a JSON file using .NET, it will require way more memory than just having the file 1-to-1 copied to memory. This was a bummer, because it meant I had to find a library which somehow manages to parse the huge JSON file without loading it completely into memory.

Because the PowerShell script was just a quick PoC and in my experience Python has many useful libraries available, I started writing a new Python script. The chophound.ps1 PowerShell script is available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/bitsadmin/chophound/.

Python importer

For memory-efficient parsing of the huge JSON file I found the ijson Python module3 to iterate through the file. Because the meta tag is required for every resulting JSON file and is located at the end of the JSON file, I first read the last 0x100 bytes from the JSON file on disk. Next, I use a regular expression to extract the meta tag, which is subsequently parsed by the JSON parser to be able to update its values.

After obtaining the meta tag, a loop iterates over the JSON file and extracts the chunks which size can be specified using the -c (long: --chunksize) parameter where the default is 500. Next, the meta tag is updated with the number of items in the current chunk after which the is stored on file on disk with a sequence number appended to the filename. The splitting process is relatively quick and results in a directory with JSON files of around 20MB each. The size of the output file varies a bit depending on both the BloodHound type (Computers, Groups, Users, etc.) and chunksize specified. The chophound.py Python script is also available at the ChopHound GitHub repository4.

Once done, I dragged the resulting files to BloodHound which happily started importing the files. However, for some reason for several of the files BloodHound still reported that they had been created using an incompatible collector.

Non-ASCII characters

Performing a binary search by splitting the erroneous file into smaller subfiles, I identified the culprit. Even though through the process I have been using UTF8-BOM as the encoding of the JSON files (just like SharpHound’s output files), BloodHound did not like special characters that were present in the JSON. Because I did not feel like investigating how to solve this issue, I resorted to writing another (ugly) script which simply replaces all non-ASCII characters in the file with question marks (‘?’), making use of a memory-mapped file to avoid any memory issues. This file is also available at the ChopHound GitHub repository4 with the name replace.py.

After running the script against the huge JSON file, removing the 3-byte UTF-8 BOM from the beginning of the file using a hex editor (HxD5) and subsequently splitting the resulting file using the previous Python script, BloodHound was finally happily ingesting all JSON files!

Some stats of the data that had been imported.

| Type | Number |

|---|---|

| Users | 500.000 |

| Groups | 1.500.000 |

| Computers | 200.000 |

| OUs | 30.000 |

| GPOs | 40.000 |

| Domains | 40 |

| Relationships | 50.000.000 |

| ACLs | 30.000.000 |

Now all data has been stored in the Neo4j database, it is time to look at how insights can be extracted.

Querying

First some words about Neo4j. Neo4j is a graph database which is very efficient at both storing nodes and relations and finding paths between those nodes. This is in contrast to a relational database which is good at storing and retrieving structured data in/from tables.

BloodHound

The most used tool for querying the graph database is the BloodHound GUI1 which using its predefined queries and path finding features can easily visualize the relations and escalation paths between the various nodes in Active Directory. Moreover, when right clicking the edges and choosing Help, the BloodHound GUI provides some hints on how the escalation can be performed.

To dive deeper in the queries performed by BloodHound, the queries can be displayed by enabling the Query Debug Mode checkbox in BloodHound’s settings. This will add the Raw Query box to the bottom of the BloodHound GUI and show the Cypher query that has been executed. The Cypher query in the box can also be updated and executed by pressing Enter. In the next section we will dive deeper into the Cypher query language.

Besides the BloodHound GUI there are also various other tools which can query the graph database to extract insights. See the table below for some examples of such tools:

| Name | Description | Url |

|---|---|---|

| BloodHound | BloodHound GUI | https://github.com/BloodHoundAD/BloodHound/ |

| PlumHound | Generate a report with actions to resolve the security flaws in the Active Directory configuration | https://github.com/DefensiveOrigins/PlumHound/ |

| GoodHound | GoodHound operationalises Bloodhound by determining the busiest paths to high value targets and creating actionable output to prioritise remediation of attack paths. | https://github.com/idnahacks/GoodHound/ |

| BlueHound | Tool that helps blue teams pinpoint the security issues that actually matter. By combining information about user permissions, network access and unpatched vulnerabilities, BlueHound reveals the paths attackers would take if they were inside your network. | https://github.com/zeronetworks/BlueHound/ |

Cypher

The query language used by Neo4j to find nodes and paths is called Cypher and the Cypher manual6 is a very useful manual which extensively describes Cypher’s syntax by providing many examples. For inspiration, it is useful to extract BloodHound’s built-in analysis queries which are stored in PrebuiltQueries.json available from the BloodHound GUI repository7. The following lines of PowerShell can be used to download this file and store the queries in a CSV which can be imported using for example Excel.

Invoke-WebRequest https://raw.githubusercontent.com/BloodHoundAD/BloodHound/master/src/components/SearchContainer/Tabs/PrebuiltQueries.json -OutFile PrebuiltQueries.json

$js = Get-Content PrebuiltQueries.json | ConvertFrom-Json

$js.queries | % { $q=$_.queryList.query -join "`n"; [PSCustomObject]@{Category=$_.category; Name=$_.name; Query=$q} } | Export-Csv -NoTypeInformation bloodhoundqueries.csv

In some cases multiple queries are listed where the result of the former queries is used as input in subsequent queries. This is for example the case for Find Shortest Paths to Domain Admins where in case of multiple domains, first the appropriate Domain Admins group needs to be selected.

Besides the analysis queries, there are also queries that are executed when performing actions in the GUI like digging deeper into the properties of a certain node. These queries are stored per type of node in the corresponding .jsx file in the same directory as the PrebuiltQueries.json file mentioned earlier7.

Using the examples in these files it is possible to customize the queries to your specific situation. This situation can be like in my case that the database is so big that a query takes forever when simply executing it against the full database. However, when adding a condition that I am only interested in the results within a certain domain, the query suddenly takes much less time.

Besides customizing queries in the BloodHound GUI, it can also be useful perform queries storing the results in a structured form. That is where the next section is about.

Cypher query tools

To perform Cypher queries, included in Neo4j are the Neo4j Browser web interface at http://localhost:7474/ and the cypher-shell command line utility. An example command line to get the name and description of all members of the various Domain Admins groups in the dataset is the following:

cypher-shell -a localhost -u neo4j -p MyPassword --format plain "MATCH (m)-[:MemberOf*1..]->(g:Group) WHERE g.objectid =~ '(?i)S-1-5-.*-512' RETURN m"

This does the job, however column names always need to explicitly specified to make it readable and further processing of the results is not trivial.

I looked around for alternative ways to perform Cypher queries and encountered the PSNeo4j PowerShell module8 by Warren F. (@psCookieMonster) which turned out to suit my needs very well. It seems this module only works well on the Windows PowerShell module (so not on PowerShell Core), which is fine as I am running the Neo4j server directly on my Windows host. Moreover, PSNeo4j works with Neo4j versions before version 4. This is because it uses Neo4j’s REST API which has been removed from version 49.

PSNeo4j can simply be installed using Install-Module PSNeo4j after which it can be loaded using Import-Module PSNeo4j. After loading the module, the connection to the database can be established using the following lines where the Get-Neo4jUser cmdlet validates whether the connection works correctly.

$c = [PSCredential]::new("neo4j",(ConvertTo-SecureString "MyPassword" -A -F))

Set-PSNeo4jConfiguration -Credential $c -BaseUri 'http://127.0.0.1:7474'

Get-Neo4jUser

Once the connection is established, queries can be performed using the Invoke-Neo4jQuery cmdlet. This makes the query from the previous example look as follows.

Invoke-Neo4jQuery -Query 'MATCH (m)-[:MemberOf*1..]->(g:Group) WHERE g.objectid =~ "(?i)S-1-5-.*-512" RETURN m'

The nice thing is that the output of the query will be an array of objects which subsequently can be processed further using PowerShell’s powerful data filtering and manipulation features. The above query can therefore be extended to output the number of users per domain in case the dataset contains multiple domains and then store the output as CSV, which can then be imported in Excel.

$DAs = Invoke-Neo4jQuery -Query 'MATCH (m)-[:MemberOf*1..]->(g:Group) WHERE g.objectid =~ "(?i)S-1-5-.*-512" RETURN m' -As Row

$DAs | group Domain | sort -Desc Count | select Name,Count | Export-Csv -NoTypeInformation DA_counts.csv

Importing in Excel can be done using the From Text/CSV button at the Data tab in Excel. Depending on the data, Excel will automatically recognize the headers. In case the headers are not automatically recognized, the first line of the CSV can be promoted to the header by choosing Transform Data in the import wizard, clicking Use First Row as Headers and then clicking the Load & Close button. Once the table is visible in Excel, it can be copied to your favorite documentation tool (OneNote in my case).

This will yield a table like the following showing the number of domain admin users per domain which can be followed up by the security teams of the respective domains to reduce the number of admin accounts per domain.

| Name | Count |

|---|---|

| BITSADMIN.LOCAL | 7 |

| ES.BITSADMIN.LOCAL | 10 |

| NL.BITSADMIN.LOCAL | 24 |

| TEST.DEV | 163 |

Likewise specific columns can be extracted, for example in the following query which shows the domain, name, display name and DN of active users that have an SPN associated with them.

$users = Invoke-Neo4jQuery -Query 'MATCH (n:User {hasspn:true,enabled:true}) RETURN n.domain, n.name, n.displayname, n.distinguishedname' -As ParsedColumns

$users | sort n.domain,n.name | Export-Csv -NoT Users_SPN.csv

Note that I have hadded the -As ParsedColumns parameter which turns the otherwise flat output into columns. When returning a full node like in the previous query (RETURN m) this parameter is not needed, and only optionally the -As Row parameter can be added to hide some superfluous metadata attributes.

To prettify the column headings, the above query can also be updated to the following:

MATCH (n:User {hasspn:true,enabled:true}) RETURN n.domain AS Domain, n.name AS Name, n.displayname AS DisplayName, n.distinguishedname AS DN

Because returning different types of nodes in the same output yields an unclear result, the following code iterates over the node types that have a description attribute which in this case is checked for sensitive information stored in there. In PowerShell, a string enclosed in double quotation marks is called an expandable string which can contain variables that are updated to the appropriate value at the moment the line of code is executed. Strings enclosed in single quotation marks are called verbatim strings and no substitution of variables is performed. That is why in this case we will use the double quotation marks to dynamically update the Cypher query.

$types = @('User','Group','Computer','OU')

$types | % {

$type = $_

Invoke-Neo4jQuery -Query "MATCH (o:$type) WHERE o.description =~ '(?i).*(password|passwd|pwd|key|pin).*' RETURN o" -As ParsedColumns | Export-Csv -NoT "Descriptions_$($type).csv"

}

This concludes the section on querying the Neo4j database using Cypher and PowerShell. In the next section we end by discussing a trick to use multiple distinct databases.

Multiple databases

You might be working on multiple assignments for which you are using BloodHound. While it is possible to simply import the domains of all assignments in a single database and query the data individually, it might get slow and messy quickly.

For that reason it is useful to use multiple databases in Neo4j. This is possible by simply using different database folders for the different projects which can be done using the steps below. I have only tested this on Windows, however probably this will also work the same way in Linux.

- Stop the neo4j service from an elevated command prompt:

net stop neo4j(PowerShell:Stop-Service neo4j) - Navigate to the

data\databasesfolder inside of the Neo4j installation folder - Rename the existing

graph.dbfolder to something else, for examplegraph.db-ProjectX - Start the neo4j service again using

net start neo4j(PowerShell:Start-Service neo4j). A newgraph.dbfolder will automatically be created - Import your data into this clean database. Whenever you want to switch back, follow these steps again renaming the existing

graph.dbfolder to for examplegraph.db-ProjectYand renaming the previously renamed folder back tograph.db

An alternative way to switch between databases is to uncomment and update the dbms.active_database=graph.db line in the neo4j.conf file inside Neo4j’s config directory. A third option is to launch multiple Neo4j instances using Docker as described at the ‘Neo4j with Docker’ page in Neo4j’s developer documentation10.

Conclusion

BloodHound is a very powerful tool for both attackers and defenders to identify unintended paths in Active Directory environments. This is facilitated by the Neo4j graph database which can be queried directly using Cypher to efficiently extract and post-process any information so it can be used by the attackers, administrators and defenders to up the ever-ongoing game of attack and defense.

All scripts mentioned in the Importing section can be found at the ChopHound GitHub page.

https://github.com/bitsadmin/chophound/

Thanks for reading and I hope you are able to use some of the tricks in your future Active Directory assignments!

References

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 1/3: Setup Linux VM for SOCKS routing

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 2/3: Configuring the Offensive Windows VM

- Living Off the Foreign Land - Part 3/3: Using Windows as Offensive Platform

- Digging for Secrets on Corporate Shares

- Dealing with large BloodHound datasets